In October, my friend Jeremy calls. He has been working for the Harris campaign in Erie, PA for the last three months. He tells me interesting things are happening, and asks me to come tell the story.

It has been so long since then. Why am I telling you this now? Maybe because there is something here I am still trying to understand, and I wonder if you can help me.

Erie is a small city on the edge of Lake Erie in Western Pennsylvania. It usually flies below the radar of national news, but journalists and campaigners swarm the city every four years. This is because Erie is a bellwether: home to a large fraction of the undecided voters who determine election results for Pennsylvania. In the previous three elections, Erie voted for Obama, Trump, and Biden. Swingy, and notoriously in lockstep with who will become the next president.

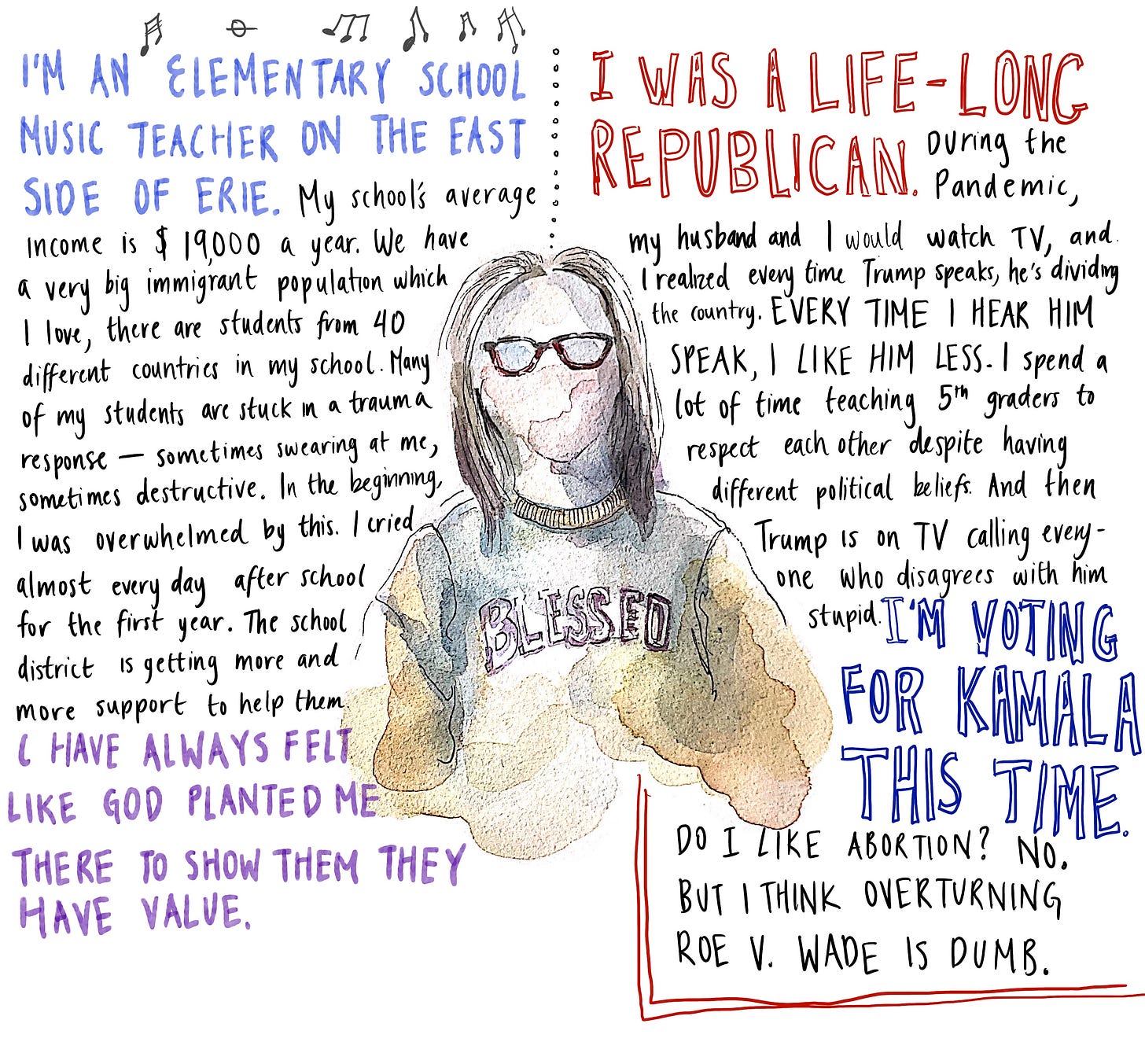

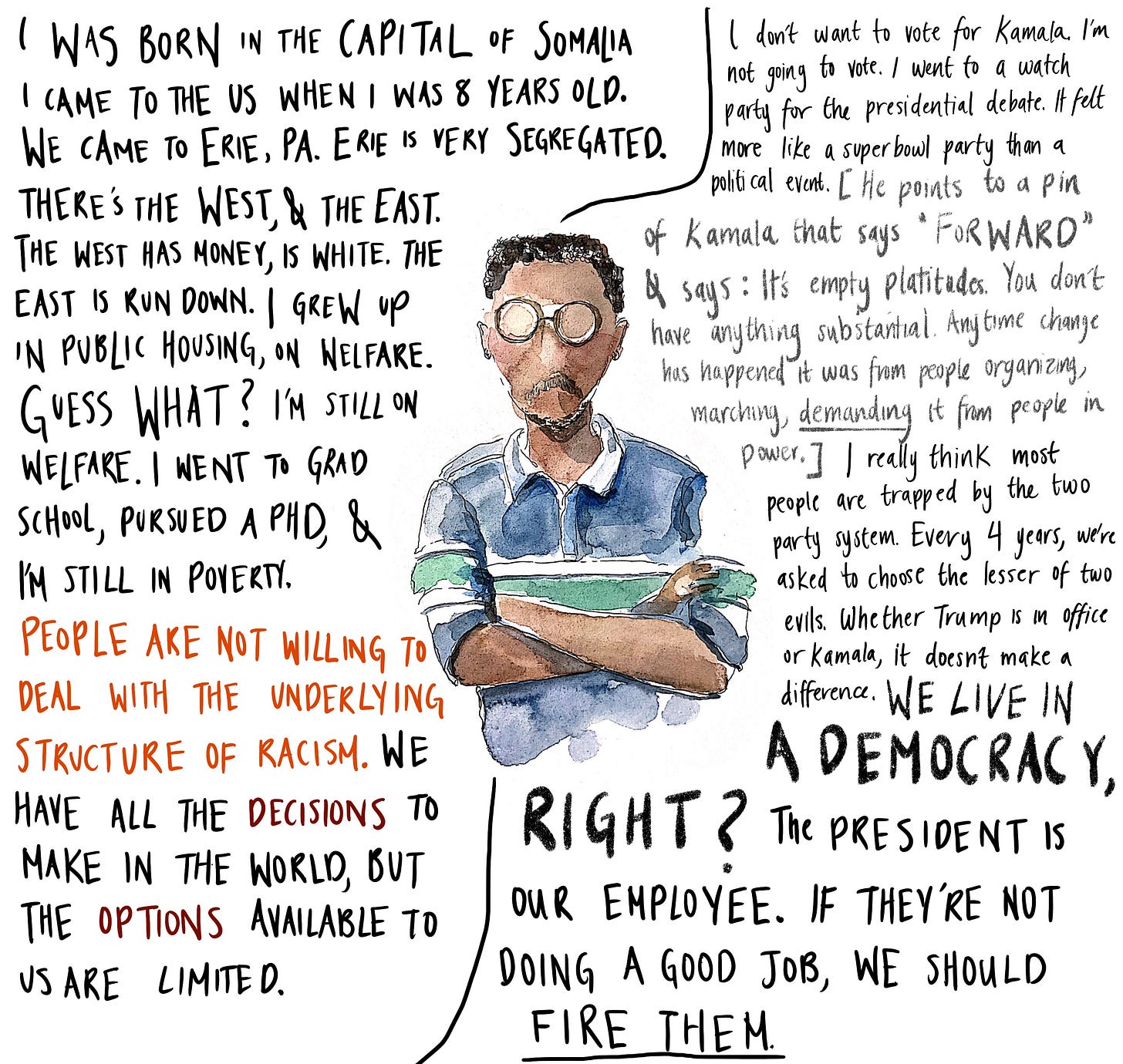

I spent a week there, canvassing for Kamala in October. I discovered quickly that I actually have no interest in pitching Kamala to undecided voters. I was more interested in listening to the people who grew up in Erie: learning why they hate Erie, love Erie, feel despair or hope or excitement or anger or gratitude for their life. I spent a week listening to them speak and drawing them. These are their stories.

In Erie, the Harris campaign is supported by a network of local democrats who volunteer as hosts, and out of town volunteers who come in for a few days or weeks to canvas. Picking me up from the Amtrak station is Wendy, my host, a retired nurse driving a small black Fiat. It’s 2am when my train arrives, and the air is cold and it is very quiet. Wendy shows me state street, the main street that divides Erie into east and west. She shows me where the campaign office is for the morning.

She drives us to her house. Warns me that there is no television, and the stairs up to my room are slippery. Her home is full of art and the sound of many clocks ticking.

At 11am, another volunteer picks me up and drives us to the Erie campaign office. Blonde and slender with a crisp voice, probably 20 or 21. He tells me he took a semester off at Harvard because he was burnt out and unsure of what he wanted to study. He drove from Cambridge to Buffalo on Friday — 8 hours on interstate 95. This is his first time canvassing on a campaign. Laughs and says so far, it’s better than doom-scrolling.

What is most striking to me about the group of campaign staff (mostly 20s) and local volunteers (mostly 60+) is their sense of urgency. Three busloads of people from Buffalo NY came to knock doors the day before. A thermostat of 60,000 doors knocked is on the wall. The other volunteer I am paired with is also new to canvassing. Cassidy, from Ohio. She tells me that the first door she knocked on this morning was slammed in her face. But she is still standing with me, clutching her clipboard, nervously tucking her hair behind her ear, practicing her script. She tells me she is an anxious person, and I notice she is shaking as we wait by the first door. I am amazed by this. How she drove 4 hours from a small town in Ohio to do something she is afraid of. The first apartment complexes we canvas are on the edge of lake Erie. Most people are not home. Or they are home — a movement of the curtains, the tv on, the sound of cupboards opening — and they do not want to answer. I don't blame them. Part of me believed it was pointless too: people do not care, they do not want to be bothered. But I look over at Cassidy, how determined she is. And for the people who do answer, most of them are kind. They tell us to keep going.

The second stop is East: the other volunteers refer to it as the projects. I ask my friend Jeremy what he means by "the projects" and he says, it means the people here are doing their best to get by. The houses are toasted red brick, small, no separation between units. There are Halloween decorations everywhere. We are inching towards late October — there are still two weekends left before the election. These are small moments that stick with me.

There is a dad who admits that he doesn't want to vote. Tells us that things are not affordable anymore, and he doesn't know what to do. A Muslim family next door peeks out curiously when they hear our voices. The woman wearing a hijab, watching us cautiously until we smile at her. She smiles back. There is an Indian woman who does not speak English, wearing an emerald sari, a red bindi on her forehead. Her front yard is full of marigolds. Her teenage daughter translates for us, listening to her mom carefully and then she laughs and says, my mother wants to vote for both candidates.

Every home is a container for an independent universe. There are smells of fried chicken and curry and sounds of reggaeton and rap and the news playing in the background. There's an African man who does not speak much English, but from what he is saying, we understand that he voted. We spend 5 minutes trying to figure out who he voted for without progress. His preteen daughter quietly tells me "he voted for the girl" after her dad went back into the kitchen.

After 5 hours, we are exhausted. Drive back to the campaign office and collapse on the floor with Styrofoam boxes: fries, fried chicken, mozzarella sticks. Tearing into them with our hands. But there is a buoyancy that was not lost – something collectively hopeful, still, at the campaign office on a Sunday night. Everyone is propelled by a belief that their actions might mean something. And when that’s true, there is always more to do.

My host Wendy loves Erie. She knows the first names of her neighbors, she knows their political beliefs, what their families are like. On my first morning, she makes me breakfast before she hosts coffee hour at the unitarian church and serves food for 200 people in the afternoon. She offers to pick me up from the campaign office at night. When I leave, she gives me a bag of honeycomb chocolates from the local chocolatier and pepperoni rolls — Erie specialties. I have never felt cared for like this by someone I just met.

There are other things I should say. Between the staff and volunteers, there were conversations about whether Harris was going to be a force of good or just better than the alternative. Most believed the latter.

The inequality and segregation in Erie was visible. State Street divided Erie into east and west, tracing a boundary between race and wealth. One voter, 18 year old, tells me the poorest zip code in the country is on the east side of Erie. I look it up later: 16501, with a median annual income of $10,873.

While canvassing, there were people who shouted for us to stay away from their home. At the time, I was too hurt to understand why. The other out of town volunteers: many recent grads, Jeremy’s friends from Harvard, mostly well-educated, ambitious, reaching for jobs in coastal cities, enjoying this brief interim in a small quiet town by the lake, a time boxed opportunity to look up from computer screens and actually talk to people, meet people living very different lives. The power dynamics, the charged nature of this, I see better in retrospect.

We are 100 days into this administration, and I think about Erie, frequently. Maybe I am nostalgic for a time before we knew who’d be the next president. When I read the news, I often have to remind myself: How complexity is flattened when we don’t listen to each other. How the most interesting conversations come from asking about someone’s fears and dreams and needs instead of their party affiliation. And someone’s political views snaps into focus, even without asking, once you understand what they are afraid of losing.

There are many ways to tell this story. One is: I came to Erie with more interest in creating an art project than understanding what it means to spend a life here. A week is not nearly long enough to reach the deep knowledge that comes from being embedded in a community.

Another way: You had to be there to feel it. There are people who seem to live very different lives but there is an entry point of connection. Each person I talked to had an openness that felt like generosity. I am reminded how we all seem to care about the future in different ways. There was a vividness to the week I spent there that I will remember. I am still thinking about the Indian woman with her marigolds, Cassidy and her fear and her bravery. I am still thinking about each person I drew, and how engaged they are with their life and their surroundings. How my world is bigger because I met them. How every regret I've ever had was from turning away from living.

I loved reading this. Such a beautiful piece of storytelling-journalism-I don’t know what to call it but it’s so full of life.

What a great experience. Work like this seems like what really makes America great.

Love how you framed this fundamental proposition.

"...complexity is flattened when we don’t listen to each other. How the most interesting conversations come from asking about someone’s fears and dreams..."

If enough of us learn this wisdom, to listen to others, we might have a chance.